1/12/2014

« Reading pile: Karbid – Berlin, from lettering to type design », par Yves Peters

I recently learned the Japanese have a word for this affliction I tend to suffer from. “Tsundoku” is the questionable habit of acquiring books without reading them, letting them pile up on shelves or floors or nightstands. I still read a lot, but because most of it happens online that doesn’t really help with the physical book situation. Though it is a little early for New Year’s resolutions, I decided to jump the gun and have been going through my reading pile lately. This is why this new series of book reviews, now on FontShop News, will be a mix of recent and less recent publications. I hope it will be good enough an excuse to help me catch up on all those tomes that tempt and taunt me on the shelves of my library.

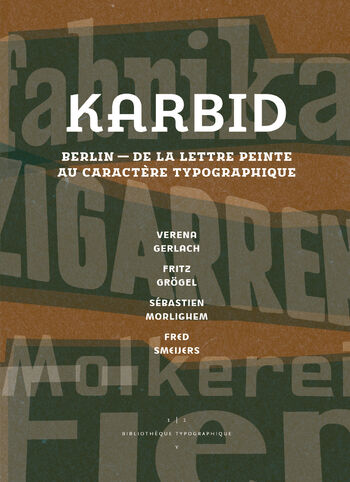

The holiday season is approaching fast, so I thought it might be a good idea to offer some tips for last minute gift shopping. And what better present for your letter-lovin’ friend or relative than a typography book? One such edition I can heartily recommend is Éditions Ypsilon’s Karbid, Berlin – From lettering to type design. So far the typography books from the French editor have not disappointed yet. Both their books on José Mendoza y Almeida and Roger Excoffon et la fonderie Olive were fantastic reads, so I had high hopes for the second release in their 1|1 imprint. The difference between the 1|1 series and the other releases from Ypsilon’s Bibliothèque typographique is that it deals with only one typeface and one designer in the context of typographic history. It examines how the forms of the past can be retrieved, revisited and revitalised in the present while eshewing nostalgia. The 1|1 editions are more than just books; they double up as elaborate type specimens.

I have always had a soft spot for Karbid, ever since I saw Verena Gerlach’s utterly engrossing presentation of the project at ATypI 2006 ”Typographic journeys” in Lisbon. Like a true typographic archaeologist Verena documented the architectural lettering in former East Berlin in the nineties. She researched, analysed and finally synthesised those eclectic sources, turning them into the original FF Karbid. The entire concept of creating a typeface as a summary of non-typographic expressions like sign painting and architectural lettering blew my mind. It elevates typeface design to another plane usually reserved to science. From that moment on I was sold on Verena and her work.

Originally published by FontFont in only three weights and one display version in 1999, FF Karbid was completely redesigned and extended in 2011. The new FF Karbid Super Family is available in four sub-families. The new FF Karbid is a harmonized redesign of the original typeface while FF Karbid Display is the most obvious spin-off of the original idiosyncratic display style. The suite of typefaces now also includes a new Slab version, and the final variant is the new Text version intended for setting body copy in small text sizes. True to their source material all versions of FF Karbid contain numerous alternate characters, allowing you to considerably change the appearance of the typefaces. These alternates are based on Art Deco lettering styles with their sometimes eccentric forms.

When I learned that not only Verena was publishing a book about Karbid, but that on top of that she was collaborating with Fritz Grögel I was very excited. After having seen Fritz’ superb presentation French Délice – Letter painting, lettering and cultural tradition in France at ATypI “Handson” (still love the logo) in Brighton, UK back in 2007 I was confident he was the ideal collaborator for this book. Having an introduction by Sébastien Morlighem was icing on the cake, the foreword by Fred Smeijers the cherry on top of it. My expectations were met, and then some…

More than merely the proverbial cherry, Fred Smeijers’ thought-provoking foreword alone is already worth the price of the admission. Smeijers questions the focus in typographic literature, past and current. He argues that instead of endlessly rehashing of the same subjects, it should adopt a more forward-looking attitude and broaden its scope. Smeijers explains printed type has an unfair advantage in academic research because its very nature means it is committed to books that can easily be preserved and consulted. More ephemeral forms of writing like lettering in the urban landscape – on posters, shop fronts, billboards, buildings… – however disappear on the rhythm of buildings being renovated or torn down. These expressions are in desperate need to be documented and researched, as they have equal importance in the history and evolution of letter forms and the written word. This why this book is important, a big step forward.

The introduction by Sébastien Morlighem does a great job at framing the book. He starts by examining “the subtle dialogue between the letters in books and the letters in the city”, then expounds on the latter – letter forms in an architectural context, and how they can be preserved. Morlighem views this in light of possible typographic revivals and makes the connection with the Karbid project, thus setting the stage for the actual book.

The main content of the book are two essays by Fritz Grögel. The painter’s letters – On history and forms of German lettering is an in-depth historical examination of (architectural) lettering in Germany. It retraces the evolution of “Schriftkunst” in the context of tools, techniques and applications. Daily life’s witnesses – Berlin letter painting portrayed situates that lettering in the urban environment of post-war Berlin. Grögel’s insightful account explains how it was possible that parts of the German capital like Prenzlauer Berg managed to be preserved as unlikely open-air museum for prewar lettering. He also examines the different forms and lettering styles typical for Berlin, and shows how this heritage is slowly being lost due to urban renovation since the reunification. Grögel reveals himself to be a fascinating researcher and storyteller. His relaxed yet knowledgeable writing style makes the book a smooth read. Because the material presented here is barely known by even an audience that is familiar with typography and type design, the book will take most readers on a delightful voyage of discovery.

Besides being an engaging book, Karbid, Berlin – From lettering to type design also is a great typeface specimen. Typefaces are best assessed in context, and having a whole book to present FF Karbid is a perfect way to discover the family in all its facets. Verena Gerlach gets the opportunity to display her chops as a book designer. The three parallel columns with respectively the French, English, and German text in three weights of FF Karbid Text work very well; all display type like titles, heads, streamers and so on showcase the other variations which are credited for easy reference. Her expressive style makes title pages pop, while the main text is subdued and very pleasant to read. Colour reproductions of many of her photographs – some of them striking enlargements – can be found at both the beginning and the end, while a map locates where they were taken. Short biographies of all the main artists mentioned in the book further increase its value as a reference work.

Amongst my favourite books about typography and lettering I have read lately, Karbid, Berlin – From lettering to type design stands out as one where I possibly have learned the most new things. I am thankful for the authors to have taken me on this fascinating journey in a lesser-known area of letter art.

For more background about the book listen to my interview with Verena Gerlach and Fritz Grögel at ATypI 2013 “Point Counter Point” in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.